The history of cooking with plant proteins has taken many forms, some of which go back hundreds of years. Products like Seitan are made from the same wheat gluten used in many meat substitutes. Historically, these were made by kneading and washing a wheat flour dough under running water until the starch washed away and mostly gluten remained. While we don’t extract wheat protein using that method today, the commercial-scale Seitan products share the same authentic origin.

Just as it has over the past 18 months, I foresee plant-based proteins continuing to grow aggressively. It appears to be the biggest topic at industry trade shows, such as IFT and SupplySide West, and is consistently a discussion point with customers over the past year. The major protein processors are also making significant financial investments and acquiring plant-based protein companies – that’s a reliable sign that plant-based products aren’t going anywhere.

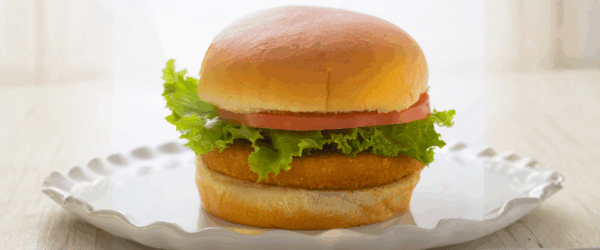

The longevity of this trend might be because of its flexibility. We have seen the progression from the early plant-based burgers in QSR evolve into a variety of other plant-based menu items and are now appearing in casual foodservice. On the retail front, the display case size is growing, and more regional players are competing. At this pace, it appears we are gearing up for a “plant-based arms race” to produce protein products without compromise to taste and texture.

Fortunately, plant-based indulgence allows us to work around creating items that we as consumers are already comfortable with. From a culinary perspective, the cuisine can stay the same, but the proteins we cook with will change. So, it’s necessary for us as chefs to understand the properties of the plant-based ingredients we’re cooking with. I like to relate these ingredients back to those we are already familiar with. For example, if we’re working with textured vegetable proteins, once hydrated, they have similar properties to cooked ground meat or poultry. If we want to make tacos, we need to season it. If we’re going to make a burger, we need to season it, add fat, and bind it together into a patty. The challenge becomes ensuring taste and texture are comparable to traditional animal proteins.

I think that’s what is most important to remember – for a plant-based burger to be successful, it has to taste good. Restaurants must look beyond this category as just the healthy, vegetarian or vegan option. That space has always existed out of necessity and has historically been the lowest volume sales. Plant-based items are an opportunity across the entire market and they have the potential to be best sellers… but it has to be good.